This unusual cabinet card portrait was taken by Philip Condon (1872-1956) of Cahir, County Tipperary. I have quite a few photographs of pet dogs in photo studios but seldom see cats in this context! The woman’s elaborate outfit typifies the extreme puff sleeve of the late 1890s.

Through a perusal of newspaper archives and the assistance of his grand-daughter, Annette Condon, I have been able to find out quite a bit about Philip Condon. He operated out of his father’s public house and contributed to amateur photographic journals in England. He won a diamond necklace for a portrait of his nephew which was published in Tatler magazine in 1904.

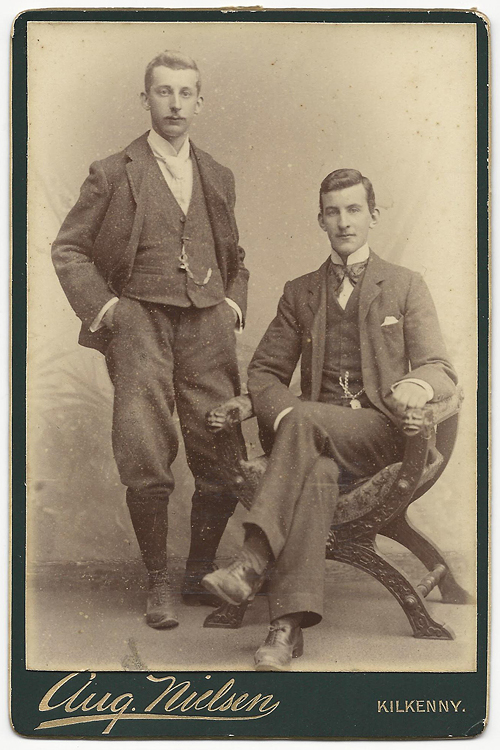

A news clipping provides a lively insight into the comings and goings at Condon’s public house and the role photography played in the town’s life. Published in The Nationalist on the1st of October 1898, it was entitled Sunday Closing Prosecution in Cahir: A Novel Defence – Drinks or Photos. The photographer’s father Patrick Condon was charged with a breach of the licencing laws as several men were found drinking alcohol on his premises in contravention of Sunday opening hours. In their defence they stated that they were waiting to have their photographs taken:

“Philip Condon, son of the defendant, was examined by Mr. Sargint, and said he was in the habit of taking photos; on the day in question he met the Buckleys and the others in the street, and they asked him to take their photos; he told them to go into his house, and he would be back in half an hour, as he had to go and take another’s photo; on his return he took the men’s photos. The defendant was examined, and said that while the men were waiting in his house for his son’s return he asked them to have a drink which he supplied at his own expense…

Mr Shoveller: ‘Do many people go to your son to get photographed? Yes, nearly every day.’ ”

Unfortunately for the Condons and the Buckleys, they were convicted and fined. This does, however, provide an indication of how novel photography was in the town at the time and Philip Condon’s relationship with his clientele!

Philip Condon appears to have been a man of remarkable energy running a pub/grocery and funeral undertakers as well as a photography studio, framing and hackney business. This hybrid of undertaking, publican and grocer was quite common outside of the larger cities and and I have found several examples, such as that of John Gannon of Cavan town who was selling Lancaster cameras and Ilford photographic plates and papers alongside coffins and wallpaper in 1895! Condon’s many interests included amateur dramatics and sport (especially cycling). He painted backdrops and sets for his photo studio and local plays. He provided photographs for a publication on The Suir from its Sources to the Sea by L. M. McCraith (1912).

Condon was married twice: firstly to Annie Carew who died in childbirth in 1917 and then to Margaret Prendergast. The funeral undertaking business remains in the family. I hope to research and write more about his photographic business and hope to trace some of his customers. His business provides an excellent example of the role of a studio in small town Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th century and also reveals how amateur and commercial photography intersected.